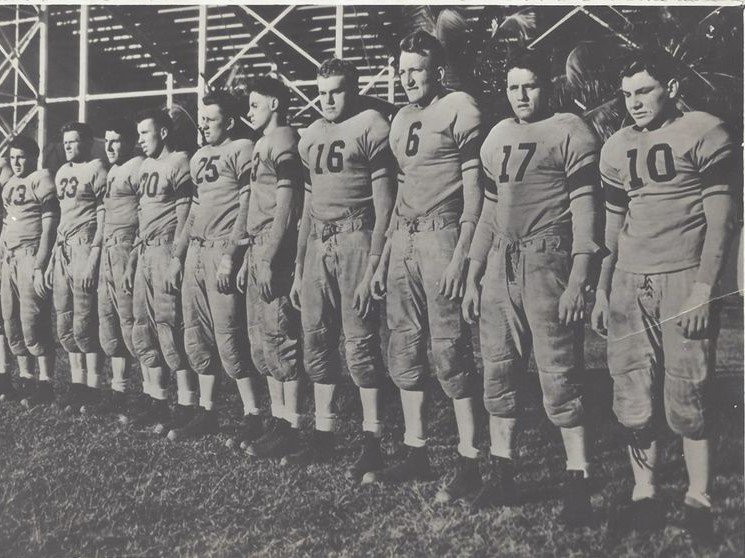

“City of Champions”, a storybook tale of leather helmets and iron wills

In 1939, two high school football teams representing Garfield, New Jersey and Miami, Florida, faced off in the Orange Bowl to decide the National Sports Foundation’s national championship. The game was a quintessential American story of immigrants, football, and gritty determination. The following is an excerpt from Hank Gola’s new book, “City of Champions”.

For seventy five years, Walter Young had something on his mind that he just couldn’t let go. He was, by that time, a very accomplished man in every respect. Yet Young always had a burning desire to do his best and a constant fear that he hadn’t. So it was that one unresolved detail weighed inconveniently on his conscience; a specter of guilt that revisited every time he looked back on a long-ago Christmas night in 1939.

The outcome was perfect that night, at least for Young and his Garfield High School teammates. The New Jersey team had already beaten the odds by just getting to the “Health Bowl,” but to have defeated powerful Miami High for the “mythical” national championship was beyond their dreams.

Now, after all those years, Young finally had the chance to salve that pesky and recurring pang of guilt. His nerves tingled so that he might as well have been sprawled on the playing surface of Miami’s Orange Bowl, when he was a raw-boned 17-year-old football player with wide eyes. All these years later, it still seemed surreal to the man peering into the glare of the laptop—and into unveiled truth itself.

Before him on his kitchen table sat a computer streaming a YouTube video. Smoky images of that game appeared in black and white, although he could easily imagine them in color— the green grass, the yellow uniforms, the blond hair of “Li’l Davey” Eldredge barely peeking out from under his tight-fitting dark blue, leather helmet, all lit up by the stadium’s soft arc lights and the blinding pops of news photographers’ flashbulbs.

Eldredge was the star of Miami’s Stingarees. Young had cut him down with the key block on a Garfield Boilermaker touchdown, leaving the two boys together on the gridiron surface, each upset for different reasons—one terribly angry, the other thoroughly frantic.

The deceptive play, with the simple, stark name of “Naked Reverse,” had worked to perfection—thanks to Young’s final role in it.

As Garfield’s left end lifted his head over Eldredge, Young could see his teammate, John Grembowitz, alone in the end zone—although he wouldn’t allow himself to admire the scene. He hurriedly scanned the field for something else: a penalty flag. There was none.

The thousands in Miami’s home crowd, unaccustomed to anything but celebrating plays, had gone silent, their usually clanging cowbells hanging by their knees. It only made the little voice inside Young’s head all the louder. Where he should have felt relief, there was dread.

“One little block,” Young explained, recalling the play in detail. “My job was to pick up Gremby as he came around left end. And he was wide open. Davey Eldredge was the kid way back, the final safety. He had the speed to catch John, and I was supposed to block him. I did. But I misjudged. He was so much faster than I was, so that instead of blocking him in a safe way, I clipped on the side. I said to myself, ‘Oh my God, I fouled him.’ I looked around and . . . no flag . . . and Gremby was over.”

With that, Young turned his attention to the video of the old game. Young admitted he hadn’t thought much about the game for long stretches. His life was too busy to dwell on it. Young was among just a few survivors from either squad when the game’s 75th Anniversary arrived and Young was invited to Garfield’s Homecoming Game to be honored at the coin toss.

In an interview that night, Young confessed to his long-held torment about the block. “But Walter, you do know that the game film is on line? That we can actually watch the play?”

So, here he was at his kitchen table as familiar images—unfolding frame by frame—filled the screen. As the video reached the third quarter, he knew what was coming.

“This is it? Yeah, by God it is! I don’t think I’ve ever seen it the way I’m looking at it right now . . . Can you stop it? . . . Now Gremby’s got the ball.”

Frozen on the left side of the screen, a shadowy figure, Garfield’s left end, can be seen. Young. Looking more closely, a solitary Miami player looms in the secondary. Eldredge. As the film progresses, they meet. Head on. Eldredge goes down. Legally. “I’ll be damned,” he said. The man who made the block asked to rewind the play over and over.

But even the proof of a legitimate victory left Young in amazement. “I still don’t know how we did it. Some day, I’m sure it’s all going to be exposed as some sort of elaborate hoax, that it never really happened,” he said with a chuckle.

Garfield’s path to a national championship was more than circuitous. It shouldn’t have happened. But, just as Walter Young’s block, it did. “Can you play it again?”

Hank Gola is a freelance sports writer who has written for the New York Daily News and the New York Post. His book, “City of Champions”, was released in November, 2018 and is available for sale in our site.

Other articles enjoyed: Tragedy Strikes College Football, Cheerleading: From Boys To Beauties, Recalling Preseason Football, Old School Days