Colombian Soccer and the Drug Lords

In a lawless country, soccer thrives thanks to the drug trade

In the 1980s and 1990s, Colombia was ravaged by an endless cycle of narco-violence that captured worldwide headlines. Yet, in the midst of this deadly scourge the game thrived and even enjoyed a golden era.

The unlikely catalyst for this phenomenon was the laundering of drug money that built soccer fields and paid top dollars for players and coaches.

At least 6 professional clubs were known to be linked with drug cartels and their sordid affairs of briberies, kidnappings, and killings.

For the merchants of death it was all part of a ‘devil-to-angel’ public relations strategy to legitimize their business dealings and gain popular support.

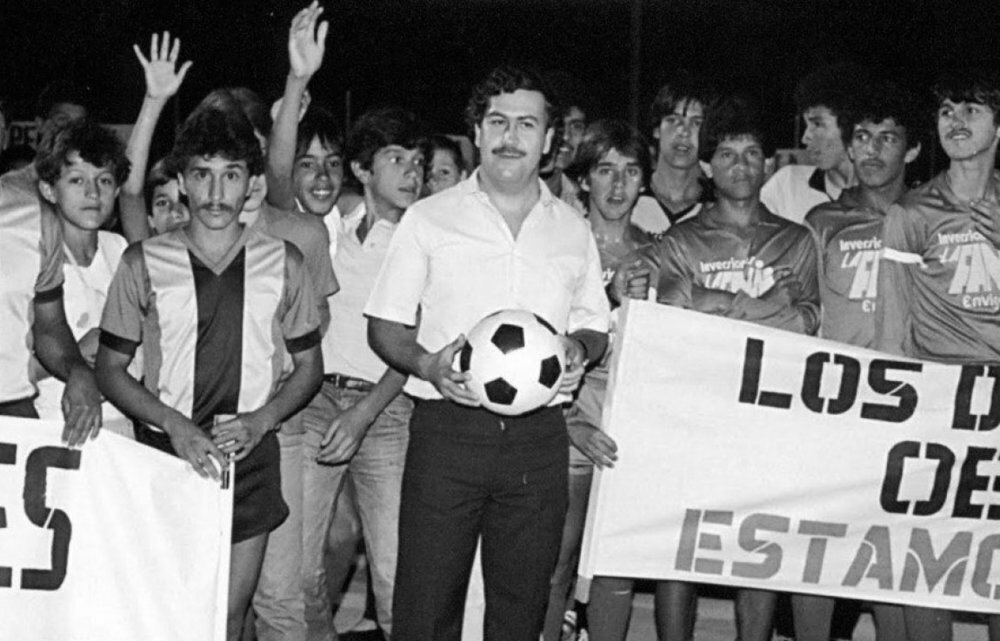

Cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar ran the Medellin-based Atletico Nacional soccer team as an open secret, funneling his proceeds from the drug trade to acquire, develop and retain the best soccer talent he could find.

At the height of his villainous career, Escobar was responsible for the majority of cocaine entering the United States and his net worth was estimated between $25-$30 billion.

At the same time, rival drug lord Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela who oversaw the Cali cartel was bankrolling another one of Colombia’s premier league teams, America de Cali.

Operating like modern-day Robin Hoods, they sponsored youth programs, built soccer facilities, and rained cash on slum neighborhoods. Though, on a business level, they washed their dirty money by financing soccer franchises, over-marking gate receipts at stadiums, and inflating player transfer fees between clubs.

In 1989, Escobar's Atletico Nacional defeated a Paraguayan squad, Olimpia, to become the first Colombian team to win South America's most prestigious club competition, the Copa Libertadores.

That year, they also claimed the Copa Interamericana and were runner-up at the Intercontinental Cup.

Following a 28-year absence from FIFA’s World Cup, Colombia qualified for three straight tournaments over the next decade: 1990 (Italy), 1994 (U.S.), and 1998 (France).

Eight of the twenty-two players who comprised the 1990 National Team played for Atletico Nacional during Escobar’s reign and they included stars such as Faustino Asprilla (forward), Andres Escobar (back), and Rene Higuita (goalie).

Even Francisco Maturana, the manager and coach of both the private and national teams, later admitted that the injection of drug money into the system raised the caliber of Colombian soccer and prevented skilled players from going elsewhere.

But soccer was still a dangerous profession in the world’s most dangerous country. The drug lords engaged in large-scale gambling activities, and matches that ended with ‘unexpected’ results were followed by deadly retribution.

In 1989, Alvaro Ortega, a referee who officiated a game between Orejuela’s America de Cali and one of Escobar’s teams, Independiente Medellin, was gunned down because he “nullified a goal…costing the chief bettors a great deal of money.”

The news sent shock waves through the soccer world and some sports writers called for Colombia to be stripped of its participation in the 1990 World Cup.

That year, FIFA and CONMEBOL, the South American Football Confederation, forced their Colombian affiliates to cancel the country’s annual premier league championship, the nation’s most watched competition.

By 1991, Escobar was forced into a plea-deal arrangement with the Colombian government to avoid being extradited to the U.S. Confined to a golden cage, he still managed to control his empire and didn’t hesitate to keep showering money on his favorite sport.

While in captivity, the underworld titan invited Diego Maradona, at the time the greatest dribbler on the international stage, to play a friendly match with Colombia’s top players.

The game was followed by late-night festivities and Maradona departed the next day with a handsome, undisclosed fee. It all took place at “La Catedral”, Escobar’s purpose-built luxury prison that featured a soccer field, a bar, a jacuzzi, and a waterfall.

Two years later, the cocaine baron was killed by police while on the run, though soccer violence had yet to reach its peak.

Colombia’s 1994 national squad was the best the country had ever assembled. Their undefeated march for the quadrennial event included a 5-0 thrashing of powerhouse Argentina, placing them at the top of the South American group.

Brazilian legend Pele even suggested that Colombia would take the trophy. But reality came crashing down on those dreams, followed by a tragic reminder that the sport was still gripped by gangland brutality.

In the opening rounds, Colombia lost to the U.S. 2-1, aided by a goal that was mistakenly deflected by defender Andres Escobar into their own net. The aspiring stars were soon eliminated and never advanced to the knockout stage.

A week later, Andres Escobar, who was also the national team’s captain, was gunned down outside a nightclub in Colombia in apparent retaliation for scoring his own goal.

Nicknamed “The Gentleman” for his clean style of play, the much-loved Escobar (no relation to Pablo) had been rumored to join A.C. Milan after the World Cup. Over 120,000 people attended his funeral.

Andres Escobar’s murder marked the beginning of the end of the "narco-soccer" period as some players quit and officials stepped up their crackdown on the sport's nefarious business affairs.

BUY- 'How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization' (National Bestseller)

Atletico Nacional was turned over to a new owner and Colombia’s international soccer ranking plummeted from a high of #4 to a low of #34 for the decade.

Dispatched again in the early rounds of the 1998 Cup, the national team settled into a long slump and was absent altogether for the next 16 years from the world’s premier soccer competition.

However, Colombian soccer came back on a resurgence in 2014 when the country made the quarter-finals for the first time and their star player, James Rodriquez, earned the Golden Boot award as the leading goal scorer in the tournament.

Atletico Nacional also reemerged in 2016 to lift the Copa Libertadores for the second time in its history and was ranked by IFFHS (International Federation of Football History & Statistics) as the best club in the world.

A dark chapter in the nation’s history, Colombian soccer under the drug lords is remembered as a sinister paradox that mixed success with tragedy and hope with despair.

ENJOY OUR CONTENT? SIGN UP FOR OUR FREE WEEKLY NEWSLETTER AND SHARE ON YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA