The Stanley Cup is Declared “not completed”

One player dies and five are hospitalized

It was the only time in Stanley Cup history that the series was declared “not completed”.

In March of 1919, the Montreal Canadiens boarded a train and crossed the expanse of North America to face off against the Seattle Metropolitans for the Stanley Cup championship. The two teams would play five games to a 2-2-1 tie when the deciding 6th match was called off.

BUY-Mark Messier autographed hockey puck

Neither the winners of the National Hockey League (NHL), nor the victors of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA), were declared champions. The influenza pandemic had found its way to the ice, sending 5 Canadian players to the hospital and killing one of the NHL’s first stars, Joe Hall.

The flu epidemic exploded in the closing year of World War I, leaving a trail of death and horror by the time it expired a year and a half later. Recognizing no borders or frontiers, the virulent microbe spread wildly across the globe, felling some 675,000 Americans and wiping out an estimated 50 million people around the world.

The armistice that ended the “Great War” was signed on November 11, 1918, just four months before the Stanley Cup championship as millions of Americans were making their way back home from the European trenches.

Few institutions were left unscathed by the infectious scourge, including those in the sporting world. One of its first athlete victims was Hamby Shore, left wing defender for the Ottawa Senators who died in the fall of 1918.

In baseball, a number of players and umpires succumbed to the outbreak, in addition to prominent sportswriters such as Eddie Martin who was one of the official scorers in the 1918 World Series, and Chandler Richter, son of ‘Sporting Life’ editor, Francis Richter.

Even Babe Ruth picked up a pneumonia after contracting the flu, though he recovered and managed to pitch a couple of series games during his illness.

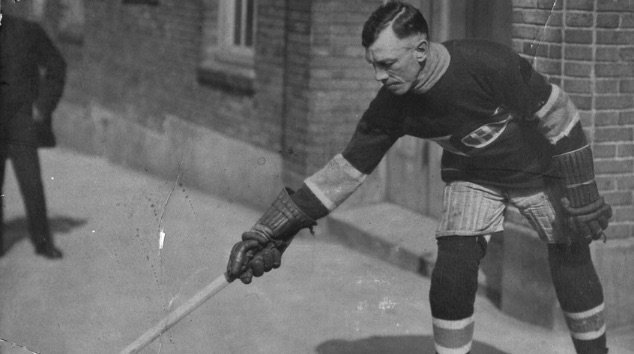

In the hockey world, 1919 seemed like a new beginning. The NHL was a newly-formed organization born out of the ashes of the National Hockey Association (NHA), an eastern Canadian league that was disband due to ongoing legal wranglings.

The old rosters were dispersed to create the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, and Ottawa Senators. The first major rule change implemented by the NHL was to permit goaltenders to drop on the ice in order to make saves, an illegal tactic under the old NHA.

The NHL’s second season saw the Montreal Canadiens defeat the Ottawa Senators for the league title, earning them a trip to Seattle for the Stanley Cup championship.

In newspapers, the public was advised to avoid contact with persons having a cold and to wash hands frequently. Colleges folded their football schedules and popular venues like bowling alleys shut their doors. But NHL games continued since hockey matches at the time were drawing relatively small arena crowds.

On the other side of the continent, the Seattle Metropolitans made it to the top of their league by taking out the Vancouver Millionaires in the PCHA playoffs. The Metropolitans defeated their cross-border rivals despite the absence of their star player, Bernie Morris.

The prolific scorer who had led his team to Stanley Cup victory two years earlier was arrested and jailed for draft dodging. He missed the PCHA series and would forcibly skip the finals against Montreal.

Seattle and Montreal weren’t strangers. They had squared off at the 1917 championship when the Metropolitans became the first American team to ever clinch the coveted trophy. Morris had scored 14 goals in that series and though legal pleas were now being made for his release so he could skate for the Mets, the government refused to grant bail and was determined to make an example of his draft evasion.

Nevertheless, both squads were talent-packed and their battle on ice proved to be one of the most intense championships in the history of the sport. The Mets fielded a trio of future Hall of Famers that included Frank Foyston (inducted 1958), goalie Harry Holmes (1972), and Jack Walker (1960).

Their opponents from the east showcased a group of puck and stick prodigies who would also be enshrined in later years. They included goalkeeper Georges Vezina (1945), whose legendary performance at the net is still commemorated today with the annual Vezina Trophy award, Newsy Lalonde (1950), one of the era’s greatest in the game, Didier “Cannonball” Pitre (1963), and “Bad Joe” Hall (1961).

On March 19, 1919, the puck was dropped to a crowd of more than 3,000 exuberant spectators who crammed Seattle’s 2,500-seat Ice Arena. No longer a front-page headline, the flu had peaked in the previous fall and was now fading from the public’s mind.

With the war behind them, Americans were eager to resume normal lives and even Seattle’s health commissioner announced earlier in the winter that the epidemic was over. But unbeknownst to many, remnants of the virulent affliction still persisted.

In Game 1, the Metropolitans thrashed their visitors 7-0, aided by Foyston’s hat-trick delivery and Holmes’ goal tending prowess. Though Game 2 saw Lalonde send 4 shots into the net to rout the Mets 4-2, Foyston came back in Game 3 with 4 goals to win it 7-2 for the home team.

Game 4 could have landed the trophy in Seattle’s hands if it weren’t for a disallowed goal in the first period. Skating to a scoreless match through 3 periods and a pair of 10-minute overtimes, players collapsed on the ice when it was over, prostrated from extreme exhaustion. Some even had to be carried into the locker room.

Three days later, in a remarkable feat of grit determination that overwhelmed an energy-sapped Seattle, the Canadiens roared back in the third period from a 3-0 deficit, tying the game and then winning it with a single goal in overtime.

The marathon series was deadlocked at 2-2-1.

The deciding match was set for April 1, but during their two days off players started to feel flu-like symptoms. Montreal’s hard-hitting defender and 17-year hockey veteran, Joe Hall, was the first to be hospitalized. He was followed by four others from his team and their general manager, George Kennedy.

With much of the squad sidelined, the Canadiens were ready to forfeit the series but Seattle’s general manager, Pete Muldoon, refused to accept the Cup under these circumstances. There was even talk of replacing the squad with members of the Victoria Aristocrats who played across the border in Canada, but the proposal was declined by the PCHA.

BUY- Wayne Cashman autographed hockey puck

With just 5 hours remaining to the start of the game, the series was officially canceled. Most of the bedridden Canadiens eventually recovered, but 37-year-old Joe Hall died four days later and George Kennedy, never fully shaking off complications from the illness, fell victim in 1921.

The 1919 Stanley Cup, forever linked to the post-war rabid flu epidemic, was memorialized with the engraved words on the trophy, “SERIES NOT COMPLETED”.

ENJOY OUR CONTENT? SIGN UP FOR OUR FREE WEEKLY NEWSLETTER AND SHARE ON YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA.